CONCEPTUAL, INSPIRATIONAL, EDUCATIONAL

PERSPECTIVES, GUIDANCE.

When AFPI Kerala asked if I would be willing to write for their newsletter, I readily agreed. I mentioned to Dr. Anoop that I would contribute something on Family Medicine/Primary Health Care research. However, on reflection, I felt a deeper need to write about the connection between our lives and daily clinical practice as family physicians with the overwhelming and urgent context of a changing planet whose natural systems are under increasing stress and in which no simple solutions are either likely or possible.

I have the good fortune of knowing and working closely with Dr. B. C. Rao and I discussed my cluttered thoughts with him and invited him to help me think through this. There was another reason I sought Dr. Rao. Besides being a source of much wisdom and encouragement, Dr. B. C. Rao also writes in a very enjoyable, conversational, and accessible manner that I felt this article deserved. It is a matter of my good fortune that he has agreed to co-author this article with me. (Note: you can find several of his writings at http://badakerecrao.blogspot.com/).

The article has been organized along three general themes: health and the wider ecological systems; diet and finally, and crucially, the role of the physician.

It weaves the related discussions from both of us: each theme begins with some reflections of Dr. Rao's over the past few decades and then introduces some critical concepts and evidence pertaining to planetary health, defined as the health of human civilization and the state of the natural systems on which it depends.

Our objectives are that by reading this article, you should be able to:

Two isolated yet related events made me write this article. The first was a tucked away news item in a newspaper which said that the central government has issued instructions that hence forth bamboo is to be preferred to wood in making furniture required for use in government offices. The other was my reading the proceedings of a symposium held during Dec 98 at Rishi valley on environmental problems.

The government order on the use of bamboo was with the intention of saving wood and there by trees which are felled legally or illegally all over the country, to make furniture and fittings, news print and for use as fuel. Vast areas of forest have disappeared to meet this demand. The universal use of tables and chairs and wooden cots in middle class Indian homes is comparatively a recent phenomenon. About 75 to 100 years ago we managed with cotton durries and cushions and used reed mattresses for sitting and sleeping. Use of chairs for sitting has brought in its wake some problems such as stiff back and hips. A sample survey of 50 men and women of middle-class were asked to squat from a standing position and the get up without support. Most of them failed this test did not come as a surprise. This is one minor example of use of furniture on health. The larger issue of cutting trees on a large scale is much more dangerous. Cutting trees results in washing away of the top soil and silting of our rivers which overflow the banks and inundate vast areas of land with loss of cultivable land and creates swamps that breed mosquitoes and you know what happens when the population of mosquito increases. There is a resurgence of malaria, filaria, encephalitis and dengue fever. There is also increase in the incidence of cholera, typhoid fever and gastroenteritis, which is due to contamination of drinking water with sewage that is common during floods.

You hear of inadvertent trespassing of whatever little wild life there is on to human habitat. This is because of destruction of their habitat partly due to encroachment and partly due to destruction of forest cover and disappearance of feeder species of plant and animal life. Bamboo furniture is not going to solve the problem. Large-scale cutting and use to make furniture out of bamboo is also not the answer, as bamboo groves naturally growing, is a link in the ecological web of the forest. The ultimate solution lies in changing our life style. Our homes need not have wood-based products. Metal can be a better substitute to wood and perhaps less ecologically damaging. Destruction of plant cover that includes forests has serious long term economic and health consequences.

To sustain minimum nutrition standards, we need to increase the grain production. We have so far done this by taking recourse to introducing hybrid high yielding crops with ample supplementation of the soil by chemical fertilizers and keeping the pests at bay by using liberal doses of pesticides. This has proved a very shortsighted success and has had disastrous long-term consequences. These pesticides and chemicals have already got into our systems and the result is that we are seeing an increase in the incidence of hitherto unknown illnesses and an increase in the incidence of cancer. The only viable solution is to use organic natural manure for which we need animal and plants and above all abundant supply of water. Many parts of our country that once sustained verdant plant and animal life is now fallow. Large areas of such land can be reclaimed not by blindly following western technology but by following methods that are relevant to our context. Efforts of a single man, Rajinder Singh has brought about an agricultural revolution to 650 villages in Rajasthan. He simply observed the natural flow of rainwater and built check bunds to slow the rate of flow and made this water collect in small and large percolation tanks. This made the water table go up and charged the wells that were hither to dry. Rishi valley is another such example. What was once barren land of dust and rocks has been successfully greened with immense economic benefits to the villages around. The same result can be seen by the work of Anna Hazare at Raalgoan Sidddi in rural Maharashtra. When once a villager becomes self-sufficient in food, his and his family's health improves and he will listen to what we talk about family planning, sanitation, nutrition etc. An empty stomach resists all attempts at progress. Thus health is linked to nutrition, which is linked to crops which are linked to the availability of water which is linked to plant cover which is linked soil retention which is linked to us not cutting trees.

All of us will be forced to realize that natural resources does not exist for man alone and this manipulation of nature that is going on world over to serve the interests of humankind will only invite disaster. When once this simple truth is understood by us and our governments, then humans will start repairing the damage to the environment, reduce their consumption and nature may forgive the injuries that she has so far suffered. If this does not happen, the humans are on their way to sure self-destruct. This article was written more than twenty years ago and is still relevant.

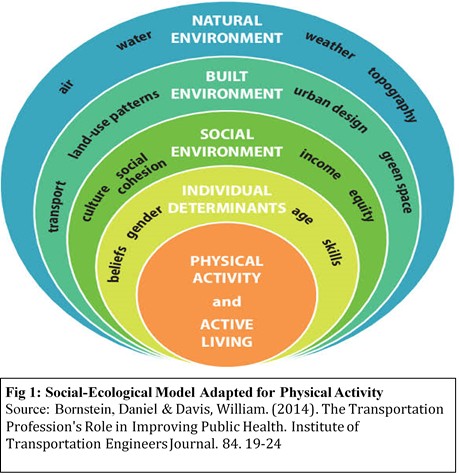

As family physicians, our daily practice cannot be separated from the context in which we and our patients and communities live. Family Medicine as a field has always been sensitive to the realization that the presentation of the patient in front of a doctor in his or her consultation room is a representation of the

sum total of his or her social, ecological (or environmental), and economic-political and health systems (Fig 1).

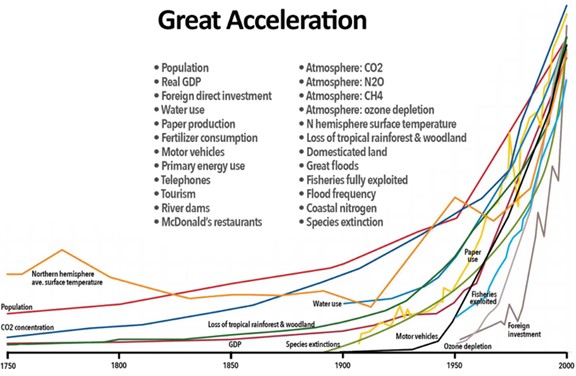

Human populations are not just growing exponentially but also urbanising dramatically. These two processes are significantly expanding the patterns consumption (and production) and driving rapid global environmental degradation, manifested in large-scale biodiversity loss, climate change, deforestation and land degradation, resource scarcity, changing biogeochemical flows, and pollution levels reaching tipping points , .

This large scale environmental degradation and loss of ecosystem services that are taken for granted such as the production of unpolluted food and water; control of climate and disease; nutrient cycles and oxygen production; and cultural, and landscapes for physical activity and spiritual and cultural connection and rejuvenation associated with access to healthy ecosystems is resulting in human health increasingly burdened by non-communicable diseases, nutritional insecurity/vulnerability, and susceptibility to displacement, injury, and mental health risks. It is notable that all of which disproportionately threaten the poor, the young, the elderly, and future generations.2

The scale of the changes above are of such a magnitude that this period of the earth’s history (not just human history) has been termed the “Anthropocene” – a geological era wherein almost all the natural systems of earth are being shaped by the human pressures and activities.

Fig 2: The “Great Acceleration” of consumption that is stressing the earth’s natural systems. Source of image: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/275775177167542214/

All this will undoubtedly impact us as individuals (and our families) and our clinical practices in a multitude of ways, some which will be obvious and some more indirectly. As a result, the article by Dr. B. C. Rao resonates deeply.

Man domesticated animals and plants [animal husbandry and agriculture] between five to ten thousand years ago. Till then he did not know where his next meal was and when. Most of the food needs were met by gathering wild fruits, edible leaves, flowers, tubers [edible roots] small life like ants, flies, moths and bigger life like fish, birds, rabbits, deer and occasionally bigger animals. At that time the food was eaten raw. Cooking was the earliest form of food processing and probably it came into being only about 20,000 years ago.

Till the advent of Industrial revolution man ate more or less unprocessed food. Gradually over the past three hundred years the food that we eat has undergone a gradual change from unprocessed mostly cereal based diet to mostly meat-based diet. This is true to western nations and not so much in eastern nations. The idea that meat based diet is healthy and cereal based diet is not healthy has taken deep roots in our thinking.

If you look at historically how the chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cancers and autoimmune illnesses have evolved, one can see a more than casual relationship to these changing food habits. In societies which eat more grain based, mostly vegetarian diet, the incidence of these illnesses is much less. Even in these societies one sees these more commonly in the affluent sections than in the less affluent.

Why are we facing a sudden epidemic of diabetes in our country? Answer is in the changing food habits. There is a sudden increase in the consumption of processed, ready to eat food. People are also eating more than what is needed for them. 40 years ago, seeing a fat youngster was a rarity. Today every other boy or girl is fat. Too much food is poison.

Adding insult to injury there is hardly any exercise. We are obsessed with the scourge called automobile. Our life revolves around this ‘convenience’. That wonderful mode of transportation, bicycle, has almost disappeared from our roads. Even the poor no longer cycle to work. Even they are becoming victims to chronic disease and diabetes is not uncommon in the urban poor. In the earlier era when men walked or cycled to work, and women spent time washing, cleaning, preparing food without any mechanical aid, they kept good health.

There was no television then and people did not sit staring at TV [aptly called idiot box]. Those who watch TV should be called idiots.

Instead of changing our dietary habits and going back to grain based occasional or no meat diet with little or no processed food we seem to be hell bent on increasing our intake of ready to eat food. Food industry is a major player in keeping our bad habits growing. Ads for wafers, oils, butter, spreads, cheese and meat burgers, pies, biscuits and confectionaries, beverages, health drinks etc. bombard us day in and day out. Even us doctors don’t spend time in trying to change the dietary habits. We are more interested in treating the illness after it occurs than preventing it. Preventive medicine and epidemiology have hardly any takers.

Therefore, my friends, if you want to remain healthy and enjoy life, change your eating habits. Eat a lot of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, limit your intake of diary and meat products, take an hour’s exercise daily and avoid watching television.

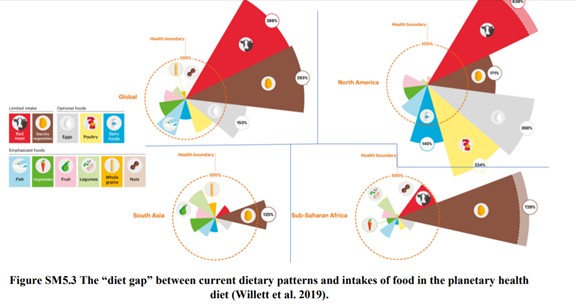

Our diet is very closely linked to not just our own health but also ecological sustainability. While on the one hand, increased food production has improved life expectancy and reduced hunger, such positive effects are being offset by major shifts towards unhealthy diets and the rising burden of obesity, non-communicable diseases, and cancer. Additionally, current food production, packaging, and distribution systems are a major factor driving climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and drastic changes in land and water use.

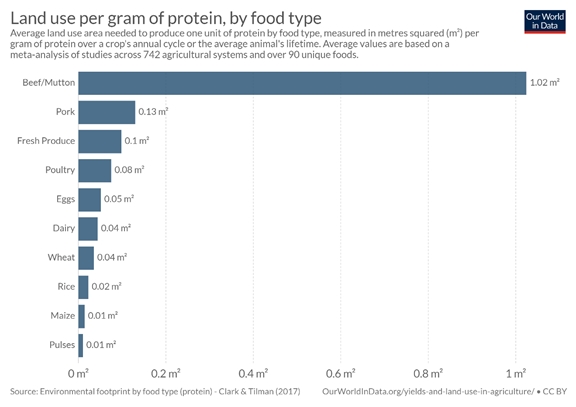

Urbanization, industrialization, and increase in dispensable have resulted in a shift away from traditional diets (which are typically higher in quality plant-based foods), to a diet characterized by high consumption of calories, highly processed foods (refined carbohydrates, added sugars, sodium, and unhealthy fats), and high amounts of animal products. Along with the negative human health impacts associated with this nutrition transition, this dietary pattern is also unsustainable. Fig 3 & 4 show the ecological costs of our dietary choices.

Fig 3. Imbalance between dietary patterns and the ability of the planet to sustain them. Source: https://medium.com/@ecyY/how-to-save-the-world-by-switching-diet-95f42514dbd7?

Fig 4: Land needed to produce 1 gram of protein by food type. Note: Pulses need 0.01 m2 whereas beef/mutton need 1.02 m2

Source: https://medium.com/@ecyY/how-to-save-the-world-by-switching-diet-95f42514dbd7?

Fig 4: Land needed to produce 1 gram of protein by food type. Note: Pulses need 0.01 m2 whereas beef/mutton need 1.02 m2

Source: https://medium.com/@ecyY/how-to-save-the-world-by-switching-diet-95f42514dbd7?

A few weeks back, I had the opportunity to travel to Southern Rajasthan to serve on an interview panel (on behalf of AFPI) for a Rural Primary Care Fellowship Program hosted by the Basic Health Services (Website: https://bhs.org.in/why-the-fellowship/). During this visit I had the good fortune of interacting with Drs. Pavitra Mohan, Sanjana Mohan, and their team that works among the tribal populations in Southern Rajasthan that has been badly affected by the “double hit” of being a highly vulnerable tribal population to begin with who are hit by large scale migration of men in these communities. Among the drivers of migration is the fact that their landscape now consists of ecologically degraded hills that are unable to support their nutritional needs.

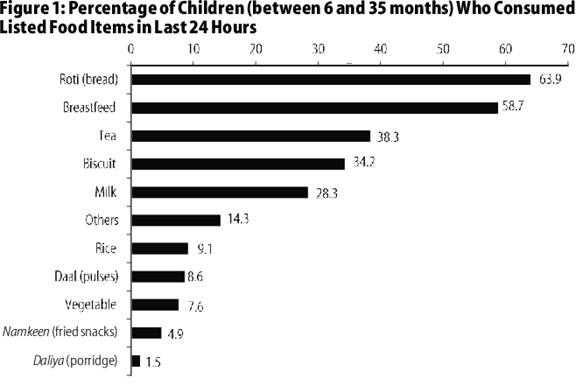

Below are some data that show the utter nutritional lack among children and mothers in these communities.

The food intake among children was noted to be highly inadequate. Based on a 24-hour food recall, children between 6 and 35 months, less than 30% of children consumed any milk. Almost none of them had consumed egg, meat or fish over last 24 hours. Fewer than 10% of the children reported consuming appropriate and nutritional food items such as daliya (porridge), rice, pulses and vegetables or fruits, and even those who consumed these items, had it in very small quantities. In addition to inadequate quantities, the eating and feeding habits were also found to be suboptimal. Many mothers reported that all they could feed their children many times were just rotis mashed with water and chilli.

Food intake among mothers was noted to be no better. Over 90% of mothers reported having eaten only 1-2 rotis in the last 24 hours. Spot assessments of food availability at the household level revealed a glaring reality of lack of food, especially nutritious food. These findings made it clear that the children and their mothers in these communities were eating extremely poorly, and that was the most immediate cause for low nutrition levels.

It was heartening to note that the team of physicians who lead BHS had responded to this by starting a number of day care centers where nutrition was made available to local children. All this again highlights the fact that beyond the clinical management of malnutrition, the social, economic, ecologic an political dimensions cannot be ignored.

Figure 4: Percentage of Children (between 6 and 35 months) Who Consumed Listed Food Items in Last 24 Hours. Source: Mohan, Pavitra and Kumaril Agarwal. “Child Malnutrition in Rajasthan Study of Tribal Migrant Communities.” (2016).

A physician, especially a primary care physician practicing in a community, wields enormous influence in that community. He can and should be a catalyst for social change.

However, just seeing patients is not enough.

If, in an 8 to 10-hour schedule of work, the doctor only sees patients, in approximately 60/70 cases, he will not make any significant contribution to improving the health and economics of the country. Neither is he going to improve as a person, a guide, and a leader of the community, nor is he going to become an example worth emulating. He will live and die within the four walls of his consulting room.

To be a powerful catalyst for change, he himself first needs to be healthy: For example, if he is not regularly exercising, his advice regarding exercise to his patients is unlikely to be followed. Similarly, if the doctor who gives advice is overweight, then giving advice on diet and weight reduction is unlikely to be followed and such a doctor has no moral right to give such advice which he himself is not following. Thus, a primary care physician who exercises and takes care of what he eats is already on his way to becoming more, to ensuring that his words are followed.

In my experience, having interests outside of medicine is useful to make one a better physician. These are interests in art, literature, music, sports, writing and doing some original work in one’s chosen field. While pursuing these diverse interests, one often finds surprising links to health. People who are adept in several fields of activity can sometimes add to the knowledge in one field because of their expertise in another. To do anything constructive, one needs time. One has to make time. This may mean spending a smaller number of patient hours and prioritizing his and his family’s needs. If seeing 25 patients in a day is more than enough to meet all his demands, then he should restrict his hours to seeing that many in a day. He can then devote the rest of his time to his own personal growth. Unless he becomes a different person in addition to just being another run-of-the-mill primary care physician (just a doctor), he will not be able to effectively influence his patients, let alone his community.

Multiple examples exist of physicians who do more, influence more than their peers, such as that of a family medicine physician couple who distribute iron and vitamin pills and protein powder to women and children of villages and have been able to witness the improvement in health in the overall community over many years, or of the retired doctor who organizes mass immunization drives in the community or of the physician who trained school dropouts as nurse assistants or of a neurosurgeon friend who after finding a dire lack of effective ambulance services, began an ambulance service with an efficient tracking system in the city a decade or so ago, which is still going strong. Incidentally this neurosurgeon is a singer and narrator of classical stories [Harikatha]. Did this expertise in different fields, in his case music, made him respond better and thus initiate a much-needed service and keep it going? According to me, yes.

Being a family doctor/primary care physician opens doors to all the sections of the society: regardless of whether your patient is poor or rich, they will still come to you. It would be unfortunate if the physician does not use the resources and networks at hand to effectively play a role in instituting or inspiring change.

In the article above, Dr. Rao has outlined four ideas of great relevance to practicing physicians:

a) Physician as a catalyst for change

b) Different and varied interests, pursued with a discerning mind, can make you a better physician;

c) Making time to pursue these interests is critical.

d) Some examples of physicians who have brought about social change/ improvement have been illustrated.

<

Fig 5 shows the CanMEDS framework that clearly illustrates the multiple hats that a family physician dons even at early stages in one’s career i.e. that of a medical expert, professional, scholar, communicator, collaborator, manager, and health advocate.

It is notable that WONCA (World Organization of Family Doctors) clearly states the role and responsibility we have towards the health of not just our individual patients but also the planet. WONCA states, “Human health is dependent on natural systems which underpin a range of essential services such as the provision of clean air and water, nutritious food, stable climates, and clean energy for development. Planetary Health is defined as the pursuit of the highest attainable standard of health, wellbeing, and equity worldwide through judicious attention to the human systems — political, economic, and social — that shape the future of humanity and the Earth’s natural systems, which define the safe environmental limits within which humanity can flourish. As family doctors we are in a unique position to promote knowledge about Planetary Health and behavior changes, which can improve both individual and Planetary Health - the so-called co-benefits - such as active transportation, low emission sources of energy and a more vegetable based diet in our patient communities. It is also imperative that Planetary Health be included in the core curriculum of medical schools, family medicine residencies and further professional development. We must strive to integrate sustainability into our individual behavior, clinical practice, and in our meetings.”

From a personal action point of view, perhaps the following practical steps can be incorporated into our daily lives as family physicians: a) Cultivating curiosity; b) Finding time for reflective practice, practice-based research, writing, teaching, and mentoring; c) Engaging with the world beyond medicine and transactional networks; d) Being mindful of our own food and where our own food comes from; e) Spending time working with the community; and f) Engaging with and encouraging others to engage with nature

In order to reconcile the complexities of the larger context (that can be overwhelming) with the more immediate needs of patient care, as physicians we will need to; a) embrace their larger role as catalysts of social and planetary health and b) bring about a paradigm shift in our personal values and skills from conventional thinking to systems thinking as listed below:

| Conventional approach | Systems approach |

|---|---|

| Oversimplifying complex and interconnected problems by specialism (or reductionism) | Cultivating a sense of interconnectedness |

|

Focusing only on: Components Facts Quantities Size or scale Efficiency Consumers |

Focusing also on: Relationships Opinions and feelings Qualities Shape and scope Equity Citizens |

|

Celebrating being a specialist skills in measurement being noticed by others |

Celebrating being a generalist ability to sense noticing others . |

| Trying to control | Aiming to catalyze |

|

Working “on the system” while “being apart” Marketing Measuring transactions (such as number of visits or number of patient encounters) |

Working “within the system” by “being a part” Building communities Nurturing relationships |

|

Belief in: Competition – to be fine I need to take care of myself Nature is a resource to be exploited by the economy Limited personal agency |

Belief in: Cooperation – when we support each other, we all will live in a better world Nature is the basis of life and we are sustained by it Power of personal leadership. |

|

Having more Defending one’s world-view |

Being happy Listening deeply to world-views different from one’s own |

Source: Adapted from the book: TRANSFORMING SYSTEMS; Why the World Needs a New Ethical Toolkit. Arun Maira. 2019.

In this article we expand the role of physicians beyond being clinical practitioner of their trade to being catalysts with significant social legitimacy and currency of community health and the wider ecological systems. We focus the primacy of how our health is intricately and inextricably linked with nature.

Finally, we conclude that a physician is not just a licensed prescriber of pills, but also a scholar, health advocate, respected pillar of society, and leader. Imagining oneself as anything less than that is not only limiting one’s own potential but also detrimental to society.

1 Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health, 2015

2 Veidis E.M., Myers S.S., Almada A.A., Golden C.D. A call for clinicians to act on planetary health (2019). The Lancet, 393 (10185), pp. 2021.

3 Mohan, Pavitra and Kumaril Agarwal. “Child Malnutrition in Rajasthan Study of Tribal Migrant Communities.” (2016).

FAMILY MEDICINE & PRIMARY CARE

AFPI KERALA MIDZONE PUBLICATION