CONCEPTUAL, INSPIRATIONAL, EDUCATIONAL

PERSPECTIVES, GUIDANCE.

Experienced and empathetic family physicians will know the best practice guidelines for the management of common conditions in ideal situations. However, they will also know how to research, adapt and modify these to suit the individual and contextual characteristics of their patients. The 3-stage assessment of a patient in family medicine is a beautiful way to find out what an individual patient’s needs really are and what management is acceptable and feasible for them- If anything can structuralise compassion in patient management then the 3-stage assessment is that! Sadly, many current guidelines do not state what should be done if the 3-stage assessment of a patient in family medicine shows that the best practices suggested may not be feasible for a specific individual. What then should a family physician do? I am presenting some case histories that hopefully will challenge family physicians to think about this crucial issue in managing their patient in the best possible way. The patients described presented to a health centre located in the lower Kodaikanal hills with the nearest referral hospital located 40km away.

Pandian (name changed) is a frail 45 years old and has chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis. He presented to our health center because he was scheduled to be given adult pneumococcal vaccine at as subsidised rate he could afford. The health worker noticed an injury to his leg casually dressed by him. When asked about the injury Pandian stated casually that an unprovoked dog bit him on the lower leg the day before. Examination of the wound showed a 2 x 2cm cuts penetrating the skin representing a Class 3 bite. The usual tetanus immunisation, wound toilet and antibiotics were given.

What do the best guidelines say about rabies prevention? The best practice guidelines recommended by the Indian Government (GOI) and WHO http://pbhealth.gov.in/guideline%20for%20rabies%20prophylasix.pdf and https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/position_papers/pp_rabies_summary_2018.pdf?ua=1, suggested that he needed post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for rabies and rabies immunoglobulin (RIG) with a minimum 3-4 visits to a heath facility.

How did these guidelines apply to Pandian? This treatment required travel to Dindigul 5 hours away. Pandian is a widower who lives alone on his ½ acre dry land in a small village in the lower Kodaikanal hills. His only son is frequently on alcohol binges, abusive and wants his father to leave the land so that he can sell it. Pandian has no source of income other than his old age Government pension. He bluntly refused to go despite explanation of the risks – it was quite clear that he really could not go to get the best treatment.

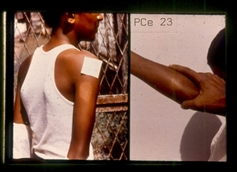

Our health centre stocks chick embryo cell culture rabies vaccine (PCEVC or Rabipur) for PEP but no RIG which is very expensive and hard to obtain. The intradermal (ID) use is known to be more rapidly immunogenic than IM route. The WHO guidelines recommend 0.1ml ID at 2 sites on days 0, 3, 7 but GOI still recommends additional dose at 28 days. Pandian was not at all considered likely to return for subsequent doses as he was not too bothered about the dog bite and had other compelling personal problems. This failure to complete a course of immunisation for rabies is a common problem that affects a staggering up to 50% of those given PEP- problems which the guidelines do not address at all.

Reconstituted rabies vaccine needs to be used within 8 hours as per GOI and WHO guidelines (even though reliable studies show that it is quite stable if kept refrigerated for at least 1-week https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11774089). So why waste the remainder of the 1ml vial of PCECV in our health centre where it is rare to have another patient with a dog bite needing PEP the same day? Would more than 2 doses 0.1ml ID be safe on day 0 and give the best insurance of protection if patients fail to return? WHO used to recommend 8 site x 0.1ml ID regime for PCECV and this was especially suited for emergency when RIG is not available. It was followed by 4 doses on day 7 and this regime was the most rapidly immunogenic at day 14 of studied ID and IM PEP regimes (even though at that time follow up doses were still recommended at day 28 and 90). https://www.who.int/rabies/en/WHO_guide_rabies_pre_post_exp_treat_humans.pdf

In fact one of the most recent review (2019) of all rabies PEP schedules revisits the 8 site ID regime on day 0 and states that it offers the best insurance if a patient defaults even after 1 dose, recommending a new 2 visit regime of 0.2ml ID at 4 sites on day 0 and 0.2ml ID at 2 sites on day 7 for PCECV rabies vaccine https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X19300738#b0055

So, what happened to Pandian? He had 0.1ml x 8 ID doses on day 0 and as expected he did not return for follow up vaccines. A further dose of 0.1ml ID 8 doses was strongly advised on day 7 but he declined. When the dog that bit him remained healthy at day 10 further follow up was abandoned as it was felt he would be unlikely to get rabies now.

Moral – We advise the GOI regime for all patients needing PEP vaccination but for those unlikely to complete current GOI or WHO guidelines and who cannot or will not access RIG, we have for several years given 8 doses ID of the 1ml PCECV rabies vaccine on day 0 and repeat this dose at day 7 whenever possible. At least then we would have done our best to prevent rabies in those who do not access standard treatment guidelines.

Valli (name changed) aged 38 lives in a rural hilly village. She has hypertension and has regular follow up visits every 6 months to ensure she takes her treatment. On one of these checks she was noticed to have a lump on the right side of the neck which moved with swallowing and was clearly a 4 cm x 2.5 cm oval firm smooth thyroid lump not causing any compression of airway or oesophagus. She dismissed it as not important saying that it had been present for >2 years. She was euthyroid.

So, what do the best practice guidelines say about thyroid lumps? The Indian endocrine society guidelines https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3079862/ are very similar to the American guidelines for thyroid lumps even though much of our population lives in circumstances very different to Americans. It suggests that all thyroid lumps >1cm diameter must (after excluding thyrotoxicosis through blood tests) be investigated with an ultrasound scan and a FNAC (fine needle aspiration cytology) if possible, with ultrasound guidance. This may seem a bit absurd given that they state 8.5% of Indian adults have such lumps and thyroid cancer affects about 1 in 10000 Indians. This would mean that we would be spending considerable time as doctors chasing thyroid lumps and subjecting significant numbers of those found to have suspicious lumps to invasive surgery with its associated risks to detect the rare thyroid cancer.

So how did these guidelines affect Valli? Valli and her husband who has chronic heart disease have one son. He is married and living away with his young family in a distant village. They are agricultural workers with no land and below poverty line. Valli is very nervous and dislikes taking any medications- it was only after considerable persuasion that she agreed to come to the health centre.

So, what happened to Valli? Valli’s thyroid lump was aspirated with view to ascertain if it was cystic and for FNAC if it turned out to be at least partly solid. It was cystic and completely cleared by aspiration with straw coloured fluid. The lump re appeared after a few days though and she was unwilling for further tests. Over 2 years the lump was monitored by measurement and for changes, but it remained unchanged and then gradually decreased in size and disappeared.

Moral: We insist on standard management guidelines of ultrasound and FNAC on all those who have clinical features where cancer risk is higher:

If they still will not agree to follow guidelines we will try and get at least an FNAC in the health centre. In doing so we will also detect cysts that have no solid component that are unlikely to be cancer. If there are no high-risk clinical features for cancer and the patient does not wish to follow standard guidelines and they are euthyroid, we will educate them to report any rapid enlargement and follow up by measurements and clinical assessment every 6 months.

This is a common question of course from those with chronic illnesses that needs to be answered with explanation. Our rule is that no patient should default for lack of knowledge about their illness, lack of access to treatment or lack of resources. If despite all these factors being accounted for, the patient chooses to not take treatment, then that decision needs to be respected unless it affects others in the community. Chinnan aged 35y (name changed) had paraesthesia in his hands and feet which started 6 months ago and was getting worse. Clinical examination and then skin smears done in the health centre showed multibacillary Hansen’s disease (Leprosy). He had to be treated effectively not just for his sake alone but for the sake of preventing spread to his community.

What do the guidelines recommend: Current WHO and GOI guidelines http://nlep.nic.in/pdf/WHO%20Guidelines%20for%20leprosy.pdf recommend 1 year of rifampicin, clofazimine and dapsone (MDT) for patients with multibacillary leprosy. These guidelines also recommend single dose rifampicin in close contacts after excluding active leprosy and TB quoting a 50% reduction in incidence of leprosy in the future in those given single dose rifampicin.

How did these guidelines affect Chinnan? Chinnan was given information and support about the diagnosis of leprosy. He was initially scared but started taking treatment regularly. His symptoms improved and after 4 months he was not very regular in coming for review and had to be recalled several times with increasing delays in collecting medication. He was a landless agricultural worker with 4 small children living in a tiny single room house. He felt compelled to work once he felt better and did not give importance to completing treatment despite explanation of the risk of relapse. About 50% of patients with leprosy default from treatment https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4331159/ Amazingly the guidelines fail to give any clear way of dealing with this issue. Examination of Chinnan his wife and children showed one child had clinical features of paucibacillary leprosy. It is very difficult sometimes to ensure that active leprosy is excluded on clinical grounds alone when contacts must be examined in less than ideal conditions at home because they rarely will come to a health facility. The guidelines state casually that single dose rifampicin in household contacts prevents 57% future leprosy provided active leprosy is excluded. This is even though household contact living in such crowded conditions have a high incidence of infection and later disease and a 57% reduction is hardly satisfactory. The guidelines also inexplicably ignore the wealth of information that once monthly supervised doses of ofloxacin and minocycline (ROM) added to the monthly doses of rifampicin in the WHO regime is well tolerated and effective in treating leprosy. The previous WHO guideline also recommends ROM was effective alternative to treat paucibacillary leprosy. ROM doses given once monthly supervised ensure that there is compliance.

What happened to Chinnan and his family? Chinnan was given the WHO MDT leprosy treatment with ROM also supervised monthly. He was often late collecting the drugs and home visits sometimes showed he did not take the daily doses of dapsone or clofazimine often forgetting to take these in his busy schedule. Despite that the dual regime he took with supervised ROM made his morphology index on skin smear became zero after 18 months when treatment was stopped – he took 12 supervised doses over this period. His children were treated with 3 months of ROM to ensure that if they had active leprosy they will be cured; though we cannot say the decision to extend ROM to 3 months instead of a single dose in paucibacillary disease (recommended by WHO in their previous guideline) is supported by evidence.

Moral: We give ROM with the WHO MDT treatment for all patients with leprosy (which is still diagnosed newly in many places in India despite false rumours that leprosy has been eradicated in India) to ensure that if they do default, they still have the best chance of cure. 3 doses of ROM are given to close household contacts and especially children to ensure that they have the least chances of developing leprosy years later when it will not be easily diagnosed by future doctors who will may not recognise this disease early in its course before it causes devastating deformities. Guidelines that are new may not give the best advice relevant to ground realities.

Ganesan (name changed) is 44y old but unfortunately, he had a myocardial infarction in 2014 due to his heavy smoking habit from the age of 14 years. He was left with poor left ventricular function and an ejection fraction of only 28%. He had class 3 effort intolerance. He was not suitable to have any interventional cardiology or cardiac bypass surgery.

What do the standard guidelines say?

So how did these guidelines apply to Ganesan? Ganesan lives in an Adivasi village in a remote community. He has a family again below poverty line as they are all agricultural workers with no land. His individual traits are that he does not like being hassled with too many tests and would default from treatment completely if even subsidised costs of treatment become unaffordable. He was therefore stabilised on losartan 50mg once daily (developed cough with ACEi which are cheaper), atenolol 25mg daily, frusemide 40mg once daily, atorvastatin 20mg once daily and aspirin 75mg once daily. He is now regular with medications 90% of the time and his effort tolerance has improved to Class 1 where he is able to do moderate amounts of physical work.

Moral: We need to know the best but be willing as family physicians to adapt them to suit each individual and their own circumstances. In this instance the minimal benefits of maximising doses of ACEi or ARB for the small added benefit would have led to default from affordable and acceptable treatment that still delivers 90% of the benefits.

I hope these case histories show why family physicians need to know the best but also unashamedly research and develop guidelines supported by evidence to ensure that where conditions are not ideal the patients still get the best chance of cure or resolution. As family doctors we could just wash our hands-off responsibility when the contextual or individual factors of patients prevent them from following the so-called best practice guidelines often written by specialists working in hospitals who may not have understood grass roots realities. However, I strongly feel that as family physicians we have a moral responsibility to ensure that vulnerable patients who cannot follow standard guidelines still deserve the right to have the best chance of being healed. We are the guardians of social justice and equity in health care and should not be afraid of researching and tailoring guidelines to suit every individual and give them the best chance.

Family Physician

KCPatty CF Primary Health Centre

Perumparai PO Dindigul Dt,

624212

Tamil Nadu

FAMILY MEDICINE & PRIMARY CARE

AFPI KERALA MIDZONE PUBLICATION

Designed by Dr. Serin Kuriakose & Dr. Zarin P.K. © All rights reserved 2020. Contact us at admin@afpikerala.in