CONCEPTUAL, INSPIRATIONAL, EDUCATIONAL

PERSPECTIVES, GUIDANCE.

Imagine that you are working in a busy primary health care clinic on a Monday morning. Many of the patients come from the same part of the town and have similar names. A patient with a common name reports to the reception desk, seeking treatment for a sore throat. The reception area is crowded and noisy and the receptionist does not hear his name correctly. She finds the medical file for a patient with a similar name and places it in the pile for the doctor. The doctor has fifty patients to see in the next three hours. When the doctor takes the file and meets the patient, he does not check to make sure he has the correct file. The patient has previously had an anaphylactic reaction to penicillin, which was recorded in his own records. The file that the doctor sees is for a patient with no history of penicillin allergy. The patient sees the patient, recognises that his symptoms and signs do not meet the Centor Criteria score for likely streptococcal infection (1), but thinks it is best to be cautious and decides to prescribe an antibiotic. He does not ask the patient if he is allergic to penicillin. The patient takes the prescription to the dispensary and is given a 10-day course of penicillin. The dispenser is not a trained pharmacist and does not ask the patient if he has any allergies. The patient is illiterate and cannot read the information that comes with the medicine. The patient takes the first tablet of penicillin, has a severe anaphylactic reaction and dies.

The provision of medical care always involves a process of several steps as well as a series of complex interactions between human beings, any one of which can go wrong. In the above scenario it is easy to observe a number of points at which, had a different course of action been taken, the catastrophic outcome could have been avoided. Asking ‘Who is to blame?’ is not helpful because staff work in imperfect systems and environments, and it is rare for fault to lie exclusively with any single individual. A better question to ask would be: ‘How can we prevent a similar outcome from happening again?’ This is the philosophy behind Significant Event Analysis (SEA).

According to the UK General Medical Council (GMC) ‘A Significant Event (also known as an untoward or critical incident) is any unintended or unexpected event which could or did lead to harm of one or more patients. This includes incidents which did not cause harm but could have done, or where the event could have been prevented.’ Studies of SEAs show that most incidents concern late or missed diagnosis, failures in communication and prescribing errors. In the UK, all doctors are obliged to report in their annual appraisal portfolios any events that fall under the GMC definition in which they were personally involved in any capacity. A doctor who does not believe he or she has any Significant Events to report in their appraisal cycle can expect to be questioned about their understanding of the ‘professional duty of candour’ (which requires doctors to be honest after healthcare harm (2) and the possibility that they may lack of insight into their practice.

However in primary care incidents that reach the GMC threshold for harm can be difficult to define and are relatively rare. Recognised challenges faced by doctors in primary care include an inevitable degree of uncertainty in diagnosis and management because patients are seen at an earlier stage of illness and often present with undifferentiated symptoms that are difficult to define and often prove to be self-limiting. The UK Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) (3) prefers to use the term ‘Learning Events’ and considers events suitable for analysis and reporting in the appraisal portfolio to be ‘any events where the practitioner can identify an opportunity for making improvements’, This can include ‘an event that went well because of luck or good organisation,’ which also provides an opportunity for the individual and the health care team to learn from the event.

A variety of templates are available to facilitate the recording and analysis of Significant Events. The steps in a template usually follow a similar pattern, as in this example:

| Table 1 Summary of Standard SEA Framework and report format recommended in NHS Scotland | |

|---|---|

| 1 |

What happened?

|

| 2. |

Why did it happen?

|

| 3. |

What has been learned?

|

| 4. |

What has been changed?

|

Factual information should be entered by the practitioner(s) directly involved, but discussion of the event should involve the whole health care team so that any actions can implemented and monitored collectively. Both the GMC and the RCGP emphasise that the value of SEA lies in being able to demonstrate that the event has led to real learning and change in systems and practice by both the individuals concerned and the organisation in which they work.

Although the recording and discussing of SEA or Learning Events is mandatory for all practitioners in the UK the evidence that this leads to improvements in patient care is surprisingly weak. An on-line search for relevant literature yielded multiple articles on how to perform SEA but little evidence for its effectiveness, beyond a general acknowledgement that reflecting on events, especially with a supportive team, is good practice, can be ‘cathartic’ for a doctor who believes he or she could have served a patient better, and may provide a sound learning experience for those most closely involved.

A study (4) of 191 SEA reports submitted voluntarily between 2005 and 2007 by GPs in the west of Scotland for feedback by trained peers described events in which patient harm had occurred in 25%, with another 48% describing events with the potential for harm. The most common events recorded were incidents that involved disease diagnosis; management and prescribing errors. Other, less frequent, events included failure to act on investigation results; communication problems; patient behaviour; administration problems; lack of easy access to equipment; incorrect use of medical records. More than half involved other health or social care agencies, with 30% of these involving secondary care providers. While 95% of the reports identified learning points, over half of the reports identified only personal learning needs for the individual doctor who had drafted the report which may reflect the educational intention behind the voluntary reporting system being studied. There was limited evidence that the wider practice team had been involved in learning from, and implementing necessary changes which could be due to a reluctance on the part of the doctor to open discussion to other health care workers if he or she perceives that in some way his / her performance has been below standard. Despite the high percentage of events that involved other agencies there was no evidence that these agencies had been engaged in the analysis of, and learning from, the event.

On February 18th 2011, Jack Adcock, a six year old boy with Down’s syndrome and a heart condition was admitted to Leicester Royal Infirmary with diarrhoea and vomiting; he died while being treated by a trainee paediatrician called Dr Bawa-Garba. Dr Bawa-Garba and an agency nurse involved in the boy’s care were found to be responsible for a series of errors leading up to Jack’s death. In November 2015 they were both found guilty of gross negligence manslaughter and given two-year suspended prison sentences. The Hospital Trust’s internal investigation did not identify any single root cause for the child’s death and recommended multiple actions to minimise risk to future patients. The investigation also highlighted the context in which the doctor’s failures had taken place, pointing out that she had recently returned from maternity leave, was working in a new hospital without receiving any induction, had worked a 13 hour shift with no break, there were problems with the IT system that made it difficult to access patients’ test results, and she lacked senior support as the on-call consultant was not at the hospital until later in the day and the registrar on duty was away on a training day with no cover provided for him. Following her sentencing, Dr Bawa-Garba’s professional registration was suspended for twelve months by the Medical Practitioners’ Tribunal (MPT). The GMC appealed against the suspension to the High Court. The High Court upheld the GMC’s appeal, deciding that public confidence in the profession demanded the higher penalty of permanent erasure from the medical register. Dr Bawa-Garba then appealed to the Court of Appeal and was successful, partly on the grounds that the MPT had acted when deciding the appropriate level of sanction to apply by taking into account the effect on her performance of the systemic failings of the hospital and others.

The GMC’s appeal to the High Court generated an angry reaction from the UK medical profession. It had come to light that immediately after Jack’s death Dr Bawa-Garba had written a remorseful, honest and thorough account of her own failings in his care in her appraisal documentation, following which she had taken concrete steps to improve her knowledge, skills and performance. The profession was concerned that her written reflections, which are supposed to be confidential, had been used by the GMC as evidence in their appeal. This turned out to be false but for a while it did shake the profession’s trust in the process of appraisal. As a result, in August 2018, new Guidance was issued by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. This Guidance emphasised that for the profession and health service to benefit from Reflective Practice it is essential that doctors must feel able to have open and honest discussions about clinical events. It also pointed out that the purpose of reflection on practice is to learn, and so the details that need to be documented for this are different from the documentation necessary for reporting or investigation of a serious incident.

Professor Sir Liam Donaldson, the former Chief Medical Officer of England said: ‘To err is human, to cover up is unforgivable and to fail to learn is inexcusable’.

I would argue that SEA is simply part of the process of continuous self-assessment against standards that should be part of the daily life of all health care professionals. As such, the potential benefits of participation in SEA for individual generalist doctors, other health care workers and the health care systems in which they work, are substantial and cumulative.

Firstly, there is good evidence that doctors who develop the habits and skills of reflecting regularly on their performance and who show insight into their strengths and weaknesses are safer, better practitioners. Learning to apply critical analysis to regularly challenge their own assumptions and beliefs about their practice helps them to see that things can be done differently or better.

Secondly, when patients and families are asked what they want after something has gone wrong in healthcare, even when significant harm or death has occurred, the majority (95% in a 2014 survey by the Medical Protection Society, a professional insurance and defence organisation for doctors) say that they want professionals to be honest and open with them about what happened, and they want to know that lessons have been learned so that future patients will not be harmed in the same way. Giving incomplete or delayed information about what happened and why makes people angry and increases the likelihood that they will take legal action against the professionals and services involved. SEA can support health care workers to be honest by guaranteeing that any errors they may have committed will not be looked in isolation, but in the context of other errors and any failures in the environment and system that may have contributed to their personal acts or omissions.

Thirdly there is also evidence that doctors experience high levels of anxiety and stress, and that some of this is related to fear of failure or of making an error that causes harm to a patient. Levels of stress are heightened by working in isolation, by poor working conditions and by having to work excessively long hours. Stressed, tired doctors are more likely to make errors, so this is a vicious circle. SEA in a supportive team environment can help to break down some of this isolation and provide a forum in which to express concerns about the working environment or systems and make suggestions for changes to improve patient care and safe practice.

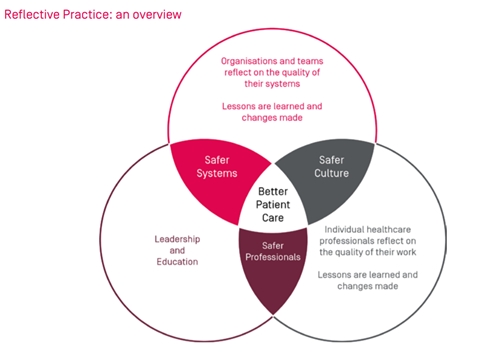

The diagram below, taken from the Reflective Practice Toolkit of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges summarises the elements and expected outcomes of reflective practice:

Significant Event Analysis applies the core professional skills of critical thinking and analysis to individual performance and health care systems. Initiation of, and participation in, the process should be part of every doctor’s commitment to maintaining professional standards. It should also inform organisational learning so that institutions and services can make system changes that lead to better services for patients, and a safer working environment for doctors and other health professionals.

FAMILY MEDICINE & PRIMARY CARE

AFPI KERALA MIDZONE PUBLICATION

Designed by Dr. Serin Kuriakose & Dr. Zarin P.K. © All rights reserved 2020. Contact us at admin@afpikerala.in