CONCEPTUAL, INSPIRATIONAL, EDUCATIONAL

PERSPECTIVES, GUIDANCE.

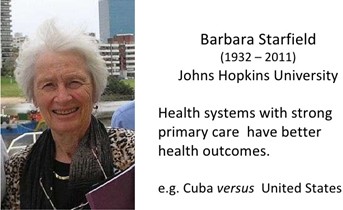

When I glanced through the book ‘Poor Economics’ by Nobel Laureate, Abhijit V Banerjee and his wife Esther Duflo, I could not help capturing some of their thoughts on health-related issues because I felt strongly that a Family Physician can be the light that dispels the darkness of Poor Economics shrouding good and equitable health-care. In this article, I have tried to capture excerpts from the book to substantiate how a Family Physician can do this at all four levels: individual, family, community and national and have bolstered this with evidence from Barbara Starfield, hailed as the ‘Pathfinder’ of Primary Care. [1]

When I glanced through the book ‘Poor Economics’ by Nobel Laureate, Abhijit V Banerjee and his wife Esther Duflo, I could not help capturing some of their thoughts on health-related issues because I felt strongly that a Family Physician can be the light that dispels the darkness of Poor Economics shrouding good and equitable health-care. In this article, I have tried to capture excerpts from the book to substantiate how a Family Physician can do this at all four levels: individual, family, community and national and have bolstered this with evidence from Barbara Starfield, hailed as the ‘Pathfinder’ of Primary Care. [1]

Excerpts from ‘Poor Economics’ (pp.64-67, 84-86): “Why are the poorest in India so small? Indeed, why are all South Asians so scrawny? 33 percent of men and 36 percent of women in India were undernourished in 2004–2005. Is this something to be concerned about? Could this be something purely genetic? After all, even the children of South Asian immigrants in the United Kingdom or the United States are smaller than Caucasian or black children. It turns out, however, that two generations of living in the West without intermarriage with other communities is enough to make the grandchildren of South Asian immigrants more or less the same height as other ethnicities. Therefore, if South Asians are small, it is probably because they, and their parents, did not get as much nourishment as their counterparts in other countries. The numbers for India from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 3) reveals that roughly half the children under five are stunted and about one in five children under three is wasted. IQ is also found to be lower in these children. What matters is good nutrition in early childhood: On average, adults who have been well nourished as children are both taller and smarter.

In Udaipur, a group of government nurses said that when a child came to them with diarrhea, all they could offer the mother was a packet of oral rehydration solution (or ORS, a mixture of salt, sugar, potassium chloride, and an antacid to be mixed with water and drunk by the child). But most mothers didn’t believe that ORS could do any good. They wanted what they thought was the right treatment—an antibiotic or an intravenous drip. Once a mother was sent away from the health center with just a packet of ORS, the nurses told us, she never came back. Every year, they saw scores of children die from diarrhea, but they felt utterly powerless.”

“Some of these technologies are so cheap that everyone, even the very poor, should be able to afford them. Breast-feeding, for example, costs nothing at all. And yet fewer than 40 percent of the world’s infants are breast-fed exclusively for six months. …A bottle of Chlorine costs $0.18 US PPP and lasts a month. This can reduce diarrhea in children by up to 48 percent…Yet only 10 percent of the population actually uses bleach to treat their water…Demand is similarly low for bed nets which not only protect the person sleeping under the net but reduce the malaria transmission of the disease and therefore bring tremendous value to a community.”

Take Home Message: We, as Family Physicians are strategically placed to address these issues by giving focused health promotion; eg. regarding right nutrition, use of ORS, safe water etc.

Evidence from Starfield: The evidence is also consistent that first contact with a primary care physician (before seeking care from a specialist) is associated with more appropriate, more effective, and less costly care. If the interest is in patients’ health (rather than disease processes or outcomes) as the proper focus of health services, primary care provides superior care, especially for conditions commonly seen in primary care, by focusing not primarily on the condition but on the condition in the context of the patient's other health problems or concerns. [2]

Excerpts from ‘Poor Economics’ (pp.87-88): In a village in Indonesia we met Ibu Emptat, the wife of a basket weaver. A few years before our first meeting (in summer 2008), her husband was having trouble with his vision and could no longer work. She had no choice but to borrow money from the local moneylender to pay for medicine so that her husband could work again, and for food for the period when her husband was recovering and could not work (three of her seven children were still living with them). They had to pay10 percent per month in interest on the loan. However, they fell behind on their interest payments and by the time we met, her debt had ballooned; the moneylender was threatening to take everything they had. To make matters worse, one of her younger sons had recently been diagnosed with severe asthma. Because the family was already mired in debt, she couldn’t afford the medicine needed to treat his condition. He sat with us throughout our visit, coughing every few minutes; he was no longer able to attend school regularly. The family seemed to be caught in a classic poverty trap—the father’s illness made them poor, which is why the child stayed sick, and because he was too sick to get a proper education, poverty loomed in”

Take Home Message: We, as Family Physicians are unique in being able to see and treat and help the family as a whole and to understand the various family dynamics and situations.

Evidence from Starfield: The characteristics of primary care practice present in countries with high primary care scores and absent in countries with low primary care scores were the degree of comprehensiveness of primary care (i.e., the extent to which primary care practitioners provided a broader range of services rather than making referrals to specialists for those services) and a family orientation (the degree to which services were provided to all family members by the same practitioner). [3]

Excerpts from ‘Poor Economics’ (pp.25-26): “To take an example, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), malaria caused almost 1 million deaths in 2008. One thing we know is that sleeping under insecticide-treated bed nets can help save many of these lives. Studies have shown that in areas where malaria infection is common, sleeping under an insecticide-treated bed net reduces the incidence of malaria by half. What, then, is the best way to make sure that children sleep under bed nets? For approximately $10, you can deliver an insecticide-treated net to a family and teach the household how to use it. Because malaria is contagious, if Mary sleeps under a bed net, John is less likely to get malaria—if at least half the population sleeps under a net, then even those who do not, have much less risk of getting infected.”

Take Home Message: We, as Family Physicians are aware that the patient we treat hails from a family which lives in a community. And we need to focus on Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) and see how we can intervene appropriately at the community level to bring about health change.

Evidence from Starfield: Those U.S. states with higher ratios of primary care physicians to population have lower smoking rates, less obesity, and higher seatbelt use than do states with lower ratios of primary care physicians to population. [4]

Excerpts from ‘Poor Economics’ (pp.102): “When faced with a serious health issue, poor households cut spending, sell assets, or borrow, often at very high rates: In Udaipur, every third household we interviewed was currently repaying a loan taken out to pay for health care. A substantial proportion of those loans are from moneylenders, at rates that can be very high: The standard interest rate is 3 percent per month (42 percent per year). The issue is not just how much the poor spend on health, but what the money is spent on, which is often expensive cures rather than cheap prevention. To make health care less expensive, many developing countries officially have a triage system to ensure that affordable (often free) basic curative services are available to the poor relatively close to their homes. The nearest center typically does not have a doctor, but the person there is trained to treat simple conditions and detect more serious ones, in which case the person is sent up to the next level.”

Take Home Message: We, as Family Physicians need to focus on cost-effective care and teamwork so as to give quality care at affordable costs.

Evidence from Starfield: Ten Western industrialized nations were compared on the basis of three characteristics: the extent of their primary health service, their levels of 12 health indicators (eg, infant mortality, life expectancy, and age-adjusted death rates), and the satisfaction of their populations in relation to overall costs of the systems. There was general concordance for primary care, the health indicators, and the satisfaction-expense ratio in nine of the 10 countries. [5]

Banerjee and Duflo talk about the 3 ‘I’s: Ideology, Ignorance, and Inertia which leads to poor economics. Ideology drives a lot of policies, and even the most well-intentioned ideas can get bogged down by ignorance of ground-level realities and inertia at the level of the implementer. They dream of next generation leaders who actually want to lead, teachers who actually want to teach and health providers who provide real access to health. We, as Family Physicians should not limit ourselves to our small practices but need to bear in mind, the big picture of health transformation of our nation and should work towards being ‘Agents of change’. We need to have ‘Health for All’ as our ideology, dispel ignorance by knowing the ground realities and overcome the inertia by actively working towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

FAMILY MEDICINE & PRIMARY CARE

AFPI KERALA MIDZONE PUBLICATION